What is the “Ukrainian Adjustment Act” that was introduced in Congress recently, and what is the status of this proposed legislation? Bill H. R. 3911, named the Ukrainian Adjustment Act of 2023, was introduced on June 7, 2023 in the U.S. House of Representatives. It was sponsored by U.S. Representatives Mike Quigley (D-IL), Bill Keating (D-MA), Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA), and Marcy Kaptur (D-OH). According to the bill’s sponsors, it was introduced “to bring stability to the lives of Ukrainians who reside in the U.S. on humanitarian parole.”

PLEASE NOTE: THIS IS NOT A LAW! THIS IS ONLY A PROPOSED BILL THAT WAS INTRODUCED IN CONGRESS.

This bill is only in the very first phase of a journey that could take years to complete — or never be completed! Since the bill was just introduced in June 2023, it has remained in the preliminary review phase.

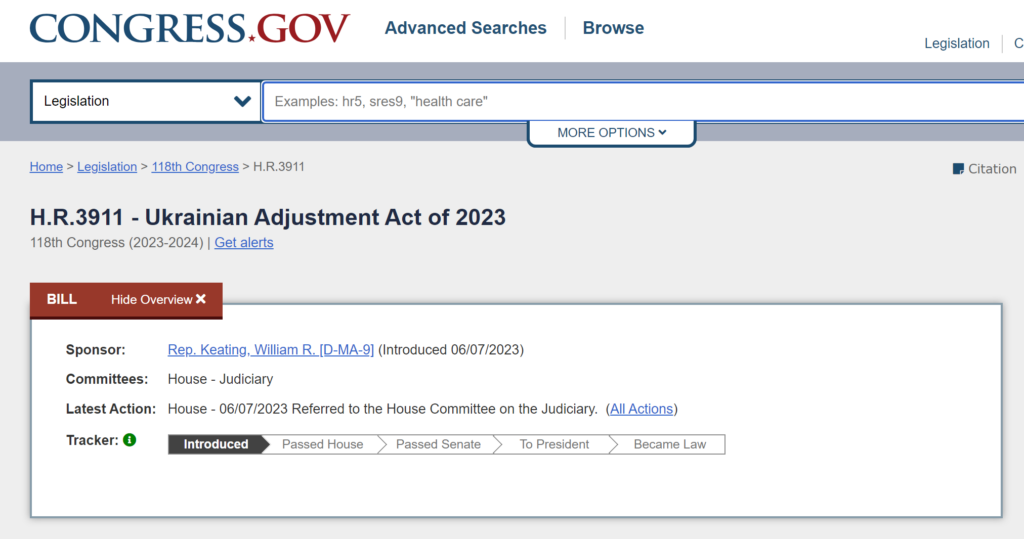

As the below graphic shows, the current status of the bill indicates the bill was “Introduced” with the latest action occurring on 06/07/2023 when the bill was “Referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary.”

Below, we provide a summary of the key points proposed in the bill, including the sections describing the proposed eligibility and procedures for applicants.

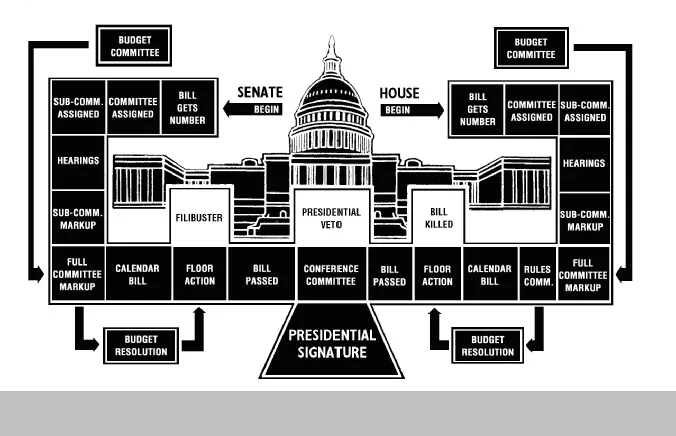

First, here is an overview of the U.S. legislative process with a brief step-by-step explanation of how an introduced bill becomes the official law of the United States.

How Does a Bill Become Law in the United States?

- A bill is a piece of legislation that a member of the House of Representatives or Senate wants to become law.

- A bill is proposed, or sponsored, by a member of the House of Representatives or Senate. The sponsor of the bill is not necessarily the author. Bills might be written by other members, staff members, interest groups, or others.

- The bill is given to the House clerk or put in the hopper in the House of Representatives. In the Senate, a Senator must seek recognition to introduce a new bill in the morning.

- In the House of Representatives, additional members may add their names to the bill to become “cosponsors.” In the Senate, bills can be jointly sponsored by more than one member.

- After the bill is proposed, the Speaker of the House or the presiding officer of the Senate will send the bill to the appropriate committee.

- The committee will add the bill to their calendar. If a bill is not discussed in committee, it is effectively “killed.”

- The committee will hold hearings on the proposed bill or the chairperson of the committee may assign the bill to a subcommittee.

- After the bill is discussed, the full committee will vote on it. If the vote passes, the committee will made revisions or edits to the bill. After the edits are made, the committee must vote to accept the changes.

If major edits are made, the committee may decide to create a new bill which will start the process over from the beginning. - The committee will then write reports about why they are in favor of or against the bill. In the House, the bill will usually go to the Rules Committee for approval. The bill is then sent back to the main chamber of the House or Senate.

- When the bill returns to the main chamber, it is placed on the calendar for debate.

- When the bill comes up for debate, the House must follow the rules put in place by the Rules Committee when discussing the bill.

- In the Senate, debate is unlimited. Senators can debate the bill for as long as they want. Sometimes Senators will use a filibuster in which they continue to talk for hours to keep the bill from being passed. A filibuster can be limited by cloture or a three-fifths vote. Cloture limits the amount of time that a bill can be debated to thirty hours more.

- After the debate, the bill is voted on.

- In the House, there must be a quorum vote first to make sure there are enough members present to conduct the vote.

- If the bill passes, it is then sent to the other chamber for deliberation and voting again.

- If the bill does not pass either chamber, it dies.

- If there are two similar bills passed by both chambers, members will meet in a Conference Committee to attempt to come to an agreement about the bills. If the committee agrees, they will write a conference report that is sent to both chambers for approval.

- If both chambers pass the bill, it is sent on to the President to sign.

- If the president signs the bill, it becomes law.

- If the president vetoes (or rejects) the bill, it will be sent back to the chamber where it originated. Each chamber has to vote on the bill again and attain a two-thirds majority to override the veto.

- The president does not sign the bill within 10 days when Congress is in session, the bill automatically becomes law.

- If the president does not sign the bill within 10 days and Congress is not in session, the bill does not become law. This is called a pocket veto.

Source: Bill of Rights Institute

How Many Bills Are Introduced Each Year, and How Many of Them Are Enacted into Law?

Historically, only a small fraction of the bills that get introduced to Congress are passed into law. The below chart shows the percentage of bills that were ultimately enacted in each session of Congress since 2009. As the chart shows, between 4% and 8% of the introduced legislation became law.

The reality is that most bills introduced in Congress never even make it out of the House or Senate committee that conducts the initial review of the proposed legislation.

Source: govtrack.us

How Long Does It Take for an Introduced Bill to Become Law?

Due to the many steps it must take through the legislative process, a bill that is introduced in Congress can take anywhere from weeks or months to years before it becomes law. If a bill is not passed during the same congressional session in which it was proposed, the bill is dropped. If that happens, the bill can only be brought back on the congressional “agenda” if it is reintroduced and goes through the whole process again. This is why less that 10% of proposed bills are enacted as laws.

As an example, S.4787, the Afghan Adjustment Act, was introduced on August 7, 2022 by by a bipartisan, bicameral group of Representatives and Senators — in itself an impressive endeavor. It was advocated and promoted by a wide variety of supporters ranging from faith-based organizations, resettlement agencies, and immigrant rights groups to businesses, veterans’ groups, and Afghan-Americans themselves — among others. The bill gained over 130 additional co-sponsors in the House and Senate. Despite its tremendous support in Congress and the urgency of the cause, Congress failed to pass the legislation in 2022. In fact, only one action was ever reported for the bill: “Read twice and referred to the Committee on the Judiciary.”

The bill was then re-introduced as S.2327 on July 13, 2023 by a bipartisan, bicameral group consisting of U.S. Representatives Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) and Mariannette Miller-Meeks (R-IA), with Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Lindsey Graham (R-SC). It gained additional supporters and now has 13 co-sponsors, including some of the most tenured members of Congress. As of today, the status remains the same as it was one year ago with the previous version of the bill: “Read twice and referred to the Committee on the Judiciary.”

Historically, about 90% of bills that are introduced each session never make it out of the initial committee or subcommittee. As illustrated, even bills which enjoy bipartisan support from high-ranking members of Congress and which are advocated by a diverse coalition of citizens don’t necessarily see much movement. Some are deemed unnecessary, others never get discussed, while others are simply forgotten.

For this reason, it is difficult to predict how long a bill will take to move through the legislative process — or if it will move at all.

What Does the Ukrainian Adjustment Act Propose to Do?

The stated purpose of the bill is “to provide for adjustment of status of nationals of Ukraine, and for other purposes.” The official website of the U.S. Congress contains a brief synopsis of the bill:

- This bill provides a streamlined process for certain Ukrainian nationals (including accompanying spouse and children) who are living in the United States to receive lawful permanent resident status.

- Specifically, the bill permits Ukrainian nationals who have been paroled into the United States after February 20, 2014, to apply for and receive lawful permanent resident status.

- Additionally, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) may waive grounds for inadmissibility (excluding certain crimes or security related grounds) for individuals who apply for status adjustment. DHS must establish vetting requirements (including an interview) for applicants that are equivalent to those under the United States Refugee Admissions Program.

- The bill also preserves eligibility for the status adjustment of certain battered spouses whose eligibility for such status stemmed from a marriage that has terminated.

- Finally, the bill requires DHS to issue guidance to implement these requirements and establishes a deadline for eligible individuals to apply for adjustment.

What Are the Key Provisions of the Act?

Below are excerpts of some of the proposed items discussed in the language of the bill.

Eligibility under the Act

- an eligible Ukrainian national for the purpose of this Act is a citizen or national of Ukraine (or a person who last habitually resided in Ukraine) who was:

- paroled into the United States after 18 February 20, 2014; or

- paroled into the United States for the purpose of accompanying or following to join as the spouse or child of an individual described; or

- the parent, legal guardian, or primary caregiver of an individual described who is determined to be an unaccompanied child; and

- has not had parole terminated by the Secretary of Homeland Security.

- An alien whose marriage to an eligible Ukrainian national described above has been terminated will be eligible for adjustment of status under this section for not more than 2 years after the date on which the marriage is terminated if there is a demonstrated connection between the termination of the marriage and battering or extreme cruelty perpetrated by the principal applicant (battered spouses protection).

- Spouses and children who have been battered or subjected to extreme cruelty will be reviewed by the Secretary of Homeland Security under section 204(a)(1)(J) of the INA and section 384 of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996.

- The Secretary of Homeland Security will establish vetting requirements for applicants seeking adjustment of status under this section that are equivalent to the vetting requirements for refugees admitted through the United States Refugee Admissions Program, including an interview.

- Upon the approval of an application for adjustment of status under this section, the Secretary of Homeland Security will create a record of the alien’s admission as a lawful permanent resident as of the date on which the alien was inspected and admitted or paroled into the United States.

- With respect to an applicant for adjustment of status, the Secretary of Homeland Security may waive any applicable ground of inadmissibility under section 212(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (other than paragraphs 2(C) or (3) of such section) for humanitarian purposes, to ensure family unity, or if a waiver is otherwise in the public interest.

- The Secretary of Homeland may not waive under this subsection any applicable ground of inadmissibility under section 212(a)(2) of the Immigration and Nationality Act that arises due to criminal conduct that was committed on or after February 20, 2014 within the United States by an applicant for adjustment of status under this section.

- Aliens granted adjustment of status under this section shall not be subject to the numerical limitations under sections 201, 202, and 203 of the INA.

Proposed Application Deadlines and Review

- A national of Ukraine who does not submit an application for adjustment of status within the timeline described above may not later adjust status under this section.

- The Secretary of Homeland Security may not charge a fee to any eligible Ukrainian national in connection with

- an application for adjustment of status; or

- employment authorization under this section; or

- the issuance of a permanent resident card or an employment authorization document.

- During the period beginning on the date on which an alien files a bona fide application for adjustment of status under this section and ending on the date on which the Secretary of Homeland Security makes a final administrative decision regarding such application, any alien and any dependent included in such application who remains in compliance with all application requirements may not be

- removed from the United States unless the Secretary of Homeland Security makes a prima facie determination that the alien is, or has become, ineligible for adjustment of status under this section;

- considered unlawfully present under section 8 212(a)(9)(B) of the IINA, or

- considered an unauthorized alien (as defined in section 274A(h)(3) of the INA.

- The Secretary of Homeland Security will provide applicants with the same right to and procedures for administrative review as are provided to applicants for adjustment of status under section 245 of the INA.

Extension of Parole and Other Statuses

- Except as provided, an individual who is a national of Ukraine will not be authorized for an additional period of parole if

- such individual is eligible to apply for adjustment of status under this section and fails to submit an application for adjustment of status by the later of 1 year after the date on which final guidance is published; or

- 1 year after the date on which such individual becomes eligible to apply for adjustment of status, except that

- an individual may be authorized for an additional period of parole if the individual seeks an extension to file an application for adjustment of status under this section within the period described above; or

- has previously submitted to a vetting equivalent of the required vetting described above.

- Nothing in this section may be construed to preclude an eligible Ukrainian national from applying for or receiving any immigration benefit to which the eligible Ukrainian national is otherwise entitled.

To read the full bill and track the status of this legislation, visit the U.S. Congress website at https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/3911/text .

What Is the Current Status of the Ukrainian Adjustment Act?

The latest action occurred on June 7, 2023, when the bill was “Referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary.”

We will continue to monitor this legislation and provide updates if the bill moves forward.

What Is the Likelihood that this Legislation Will Move Forward?

It is estimated that 90% of bills that are introduced in each session of Congress never move past the initial stage of committee review. Historically, between 4% and 8% of introduced legislation actually became law.

Based on these statistics, most bills that are introduced in the current session of Congress will not progress past the initial stage, and even fewer bills will be signed into law.

What Will Happen If the Ukrainian Adjustment Act Is Not Passed?

Other avenues for permanent residence in the United States may be available to Ukrainians who meet the eligibility criteria. Learn more in our article here: https://ukrainetaskforce.org/options-for-humanitarian-parolees-to-remaining-in-the-united-states-after-uniting-for-ukraine/

Additionally, certain short-term protections such as Temporary Protected Status (TPS) can help Ukrainians remain in the United States until it is safe to return home. Read more about TPS in our article here: https://ukrainetaskforce.org/ukraine-s-temporary-protected-status-tps-is-redesignated-with-new-eligibility-dates-and-extended-for-current-tps-holders/