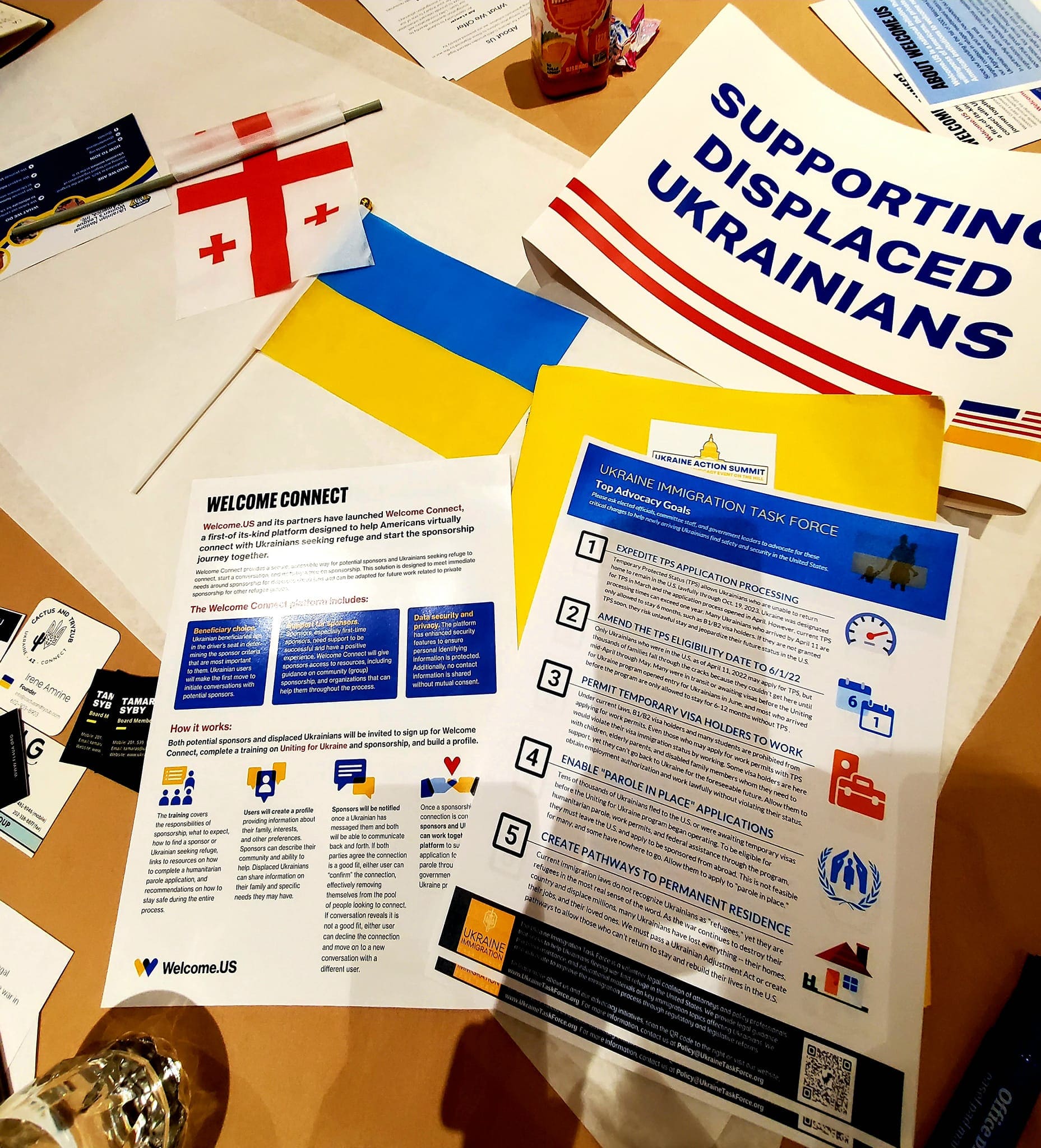

The Ukraine Immigration Task Force proposes the following regulatory actions to ensure safety and security of Ukrainian citizens seeking refuge in the United States:

Proposed Regulatory Action

1. Redesignate Ukraine for TPS as soon as possible and simultaneously extend the current term eligibility date to January 1, 2023.

Problem: Many humanitarian parolees and B-2 visa holders were only able to come to the U.S. after April 11. In fact, some of the largest waves of Ukrainians entered between April 12 and April 25, with a trickle of families who were admitted later after being detained. Those present in the U.S. on a B-2 visa risk overstaying their 6-month allowed stay, while those admitted at the southern border were only granted humanitarian parole for one year.

Policy Justification: The simultaneous extension and redesignation are warranted because the extraordinary and temporary conditions supporting Ukraine’s TPS designation remain.

Moreover, recent intervening events such as escalated terrorist attacks, annexation of 4 provinces, the imposition of martial law, and increased permanent displacement in most population centers warrant urgent action for immediate redesignation. This makes return to Ukraine impossible for millions of persons displaced or unable to return to a Ukraine-controlled territory.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the occupying military regime has widely committed human rights violations and abuses, including widespread rape, torture, murder, and the unwarranted use of deadly force against unarmed individuals. Millions of Ukrainians are unable to return to their homes because they were destroyed or because their home communities lack all essential infrastructures to provide safe shelter, and millions more face severe food insecurity.

As a result, more than 12 million people have been internally displaced, with at least 7 million seeking refuge outside of Ukraine since the invasion. Internally displaced persons and other vulnerable populations throughout the country now lack adequate and secure access to shelter, food, water and sanitation, health care, and education. Externally displaced persons are increasingly vulnerable to trafficking, crime, and exploitation.

As further support for extension and redesignation of TPS for Ukraine, Russia announced the annexation of four Ukrainian provinces on September 30, 2022.

Legal Justification: Section 244(b)(1) of the INA, 8 U.S.C. 1254a(b)(1), authorizes the Secretary, after consultation with appropriate agencies of the U.S. Government, to designate a foreign state (or part thereof) for TPS if the Secretary determines that certain country conditions exist. The decision to designate any foreign state (or part thereof) is a discretionary decision, and there is no judicial review of any determination with respect to the designation, termination, or extension of a designation.

In applying 8 USC 1254a, Section (b)(1) states that TPS may be granted when ongoing armed conflict within the state makes it unsafe for citizens to return. Ukraine’s ongoing war after Russia’s invasion creates an unsafe situation for citizens of Ukraine to return. As of now, there is no end to the war in sight.

In addition to extending an existing TPS designation, the Secretary, after consultation with appropriate Government agencies, may redesignate a country (or part thereof) for TPS if conditions support such a designation. At least 60 days before the expiration of a foreign state’s TPS designation or extension, the Secretary, after consultation with appropriate U.S. Government agencies, must review the conditions in the foreign state designated for TPS to determine whether they continue to meet the conditions for the TPS designation.

Russian’s annexation of four Ukrainian provinces on September 30, 2022 presents an additional intervening event that warrants reconsideration of Ukraine for TPS.

Precedent: Burma’s TPS designation was just simultaneously redesignated and expanded on Sept. 27, 2022. Federal Register :: Extension and Redesignation of Burma (Myanmar) for Temporary Protected Status. “The redesignation of Burma allows additional Burmese nationals (and individuals having no nationality who last habitually resided in Burma) who have been continuously residing in the United States since September 25, 2022 to apply for TPS for the first time during the initial registration period described… Individuals who have a Burma TPS application (Form I-821) and/or Application for Employment Authorization (Form I-765) that was still pending as of September 27, 2022 do not need to file either application again. If USCIS approves an individual’s Form I-821, USCIS will grant the individual TPS through May 25, 2024. Similarly, if USCIS approves a pending TPS-related Form I-765, USCIS will issue the individual a new EAD that will be valid through the same date.”

Proposed Regulatory Action

2. Prioritize TPS processing for humanitarian parolees and B-2 visitor visa holders who entered the U.S. before May 2022.

Problem: Ukrainian applicants who were eligible to apply for TPS arrived in the U.S. by April 11, and many of them are still waiting for USCIS to process their applications. Some of these applicants have already overstayed their allowed visits, and many more face expired stays between October and December 2022. Currently, TPS processing times range from 8-14 months due to USCIS application backlogs. Those who remain unlawfully longer than 180 days will accrue unlawful presence and trigger a 3 to 10-year bar to re-entry when they eventually depart, unless they obtain some immigration status. Hence, if B-2 visa holders are not granted TPS before their stay expires, they risk accruing unlawful presence after 180 days of their overstay. This could have catastrophic consequences, since these individuals risk being denied re-entry to the United States on the B-2 visitor visa they currently hold. It also jeopardizes their eligibility for other life-saving paths of entry such as Uniting for Ukraine and non-visitor visas based on family reunification.

Some Ukrainians present on a B-2 visa have applied to extend their stays. However, due to the same USCIS backlogs that delay TPS processing, renewals could take 4-8 months and would not be granted before their stay expires. If and when applicants are granted extensions, the longest they may extend their visa stay is 6 months before being forced to leave the U.S. Those who are denied renewals are required to depart the U.S. within 30 days.

Additionally, the vast majority of TPS determinations are granted only as of the day of approval, rendering many whose status expires before then potentially ineligible for future immigration relief such as Uniting for Ukraine, non-visitor visas, permanent residence, and even returning on the same B-2 visa.

Policy Justification: Ukrainians here on B-2 visas are most in danger of falling out of status, which goes against the intent of the administration and its agencies. Hence, B-2 visa holders are most in need of priority TPS processing, since they were only granted entry for up to 6 months and any renewal applications filed could take 4-8 months. Those whose renewals are denied would be required to depart voluntarily or be considered deportable.

Unfortunately, many of those whose stays have or will expire imminently have nowhere to go due to the ongoing war, with no end in sight. For some, their homes have been destroyed or their provinces annexed by Russia. Even those who could theoretically return to Ukraine may lack the financial means to do so, a challenge exacerbated by not being able to work for an extended time and, often, needing to support children or other dependents. For families with children, elderly relatives, and disabled individuals, it could be unfeasible and unsafe to travel outside of the U.S.

Even those who could somehow leave the U.S. and find safe refuge elsewhere temporarily – and could afford the costs of departing, re-arriving, and lodging for themselves and their families – they would not be able to return to the U.S. for 90-180 days due to the travel restraints of a B-2 visa.

Legal Justification: The Homeland Security Act of 2002, Pub. L. 107–296, dismantled the Immigration and Naturalization Service and created USCIS to enhance the security and efficiency of national immigration services by focusing exclusively on the administration of benefit applications. With this Act, Congress granted USCIS authority to administer the lawful immigration system. On March 1, 2003, USCIS assumed responsibility for the immigration service functions of the federal government.

Insert language from policy manual: Chapter 5 – Requests to Expedite Applications or Petitions | USCIS

Precedent: On July 28, 2022, USCIS announced priority processing of EADs for humanitarian parolees who file an I-765 online. This action uses the c(11) designation to flag and move applications from “public interest” parolees to the front of the processing queue. Since this is a fair and equitable method that doesn’t favor any one country or origin but instead helps numerous humanitarian parolees, USCIS can argue that this action is well within its authority and promotes the intended policy of the statutes.

There is both precedent and need to enable online filing for TPS as has been enabled for EADs, Uniting for Ukraine sponsorship, and Venezuelan parole sponsorship, among other forms. Online filing facilitates a flagging mechanism to identify TPS applicants with B-2 status and move their applications to the front of the queue for processing.

Since TPS filing is currently only allowed by mail, flagging could only be done by creating a new lockbox/mailing address for B1/B2 visa holders applying for TPS. However, there is already ample precedent for creating designated mailing addresses for applications that warrant priority processing. In conjunction with setting up a dedicated lockbox/mailing address, there is precedent for allowing applicants to send a PDF of the application and evidence of mailing or other delivery method.

Proposed Regulatory Action

3. Publish an Employment Authorization notice from DHS to ICE creating a “Severe Economic Hardship” exemption to allow B-2 Visa Holders who are granted TPS and issued EADs to work lawfully without violating their visa statuses.

Problem: Tens of thousands of Ukrainians have fled to the U.S. on B-2 visitor visas, either because they already had these visa applications pending with the State Department or because they didn’t know that the Uniting for Ukraine program would be created. Some couldn’t wait for a sponsor to be approved once the program was functionally operational, while others didn’t have anyone available to sponsor them.

These B-2 visa holders arrived in the U.S. expecting to stay for only 6 months, but now they cannot leave the U.S. because they had no safe place to go. Most B-2 visa holders from Ukraine are women, and many are here with children, elderly parents, or disabled family members to support. They have not been able to work since fleeing the war in Ukraine, and they have no means by which to support themselves. Nor as they eligible for federal assistance that are provided to those on humanitarian parole. Hence, these tens of thousands of B-2 visa holders – as well as their dependents – are highly vulnerable to exploitation, abuse, crime, and trafficking.

Policy Justification: Under current laws, B-2 visa holders are prohibited from working. Even those who apply for work permits with TPS would violate their visa immigration status by working.

Unfortunately, parole in place is not a remedy available to B-2 visa holders present in the U.S. to take advantage of humanitarian parole, which would grant them the right to apply for employment authorization. “Parole in place” is a temporary right to remain in the U.S. (in one-year increments) by applying to stay rather than having to leaving the U.S. and apply for a different status. Currently, “parole in place” is only available to noncitizen spouses, parents, and unmarried minor children of U.S. citizen members of the U.S. military (current or past) a path to a U.S. green card if they are in the U.S. with unlawful entry.

In order to apply for humanitarian parole through the Uniting for Ukraine program, applicants are required to be present outside of the U.S. It is unfeasible, and in some cases, impossible for many B-2 visa holders to leave the U.S. in order to apply for Uniting for Ukraine. Furthermore, such applicants would need to obtain a qualified and willing U.S. sponsor quickly who would be willing to file a sponsorship petition.

There is no policy justification for allowing only some of the individuals who qualify for TPS based on ongoing devastation and physical danger in their home countries to take advantage of the rights accorded with TPS. All individuals who are placed in the unexpected and extenuating circumstances of needing to remain in the U.S. on TPS should be able to benefit from its full rights and protections.

Legal Justification: The Homeland Security Act of 2002, Pub. L. 107–296, dismantled the Immigration and Naturalization Service and created Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to oversee immigration enforcement and border security. DHS has authority to issue guidance to ICE about how to enforce employment by aliens.

Precedent: On April 19, 2022, DHS published an “Employment Authorization for Ukrainian F–1 Nonimmigrant Students Experiencing Severe Economic Hardship as a Direct Result of the Ongoing Armed Conflict in Ukraine” in the Federal Register (see Federal Register :: Employment Authorization for Ukrainian F-1 Nonimmigrant Students Experiencing Severe Economic Hardship as a Direct Result of the Ongoing Armed Conflict in Ukraine and the accompanying press release, DHS Issues Special Student Relief Employment Benefits for F-1 International Students from Ukraine and Sudan | Study in the States.) This notice also provided new enforcement instructions to ICE (see bcm2204-03.pdf (ice.gov)).

The exemption “temporarily suspend[s] the applicability of certain requirements governing on-campus and off-campus employment for F–1 nonimmigrant students whose country of citizenship is Ukraine who are present in the United States in lawful F–1 nonimmigrant student status … and who are experiencing severe economic hardship as a direct result of the ongoing armed conflict in Ukraine. Effective at publication, suspension of the employment limitations is available through October 19, 2023, for those who are in lawful F–1 nonimmigrant status.”

DHS can issue a similar notice temporarily suspending employment prohibitions to B-2 visa holders who are granted TPS and can demonstrate severe economic hardship. DHS can also issue enforcement instructions to ICE regarding this suspension.

Proposed Regulatory Action

4. Expedite advance parole for individuals needing emergency travel authorization to reunite with family in Ukraine, make advance parole multi-entry and make the application eligible for a fee waiver.

Problem: Some Ukrainians who managed to escape and arrive in the U.S. suddenly find themselves facing a need to leave the U.S. to travel to Ukraine or other countries before they are able to obtain advance parole travel authorization. Those who need to leave the protection of the U.S. primarily do so for unexpected emergencies, such as having to take care of seriously ill family members, those severely injured by the ongoing war and terrorism, or needing to see family members who are fighting on the front lines whom they may never see again.

Those Ukrainians who arrived at the border between February and April 2022 were only granted humanitarian parole for one year, while those who arrived through Uniting for Ukraine starting in June 2022 were granted parole for up to two years.

Unfortunately, applications for advance parole can take months to approve. Moreover, the substantial $575 application fee for each person traveling with the applicant, including children, is prohibitive for many Ukrainians who recently arrived and have little or no income. As a result, some Ukrainians are forced to leave the U.S. due to emergency reasons without obtaining advance parole, thereby violating their humanitarian parole status and jeopardizing their ability to return.

Policy Justification: Ukrainians who need to leave the safety of the U.S. are already under great distress after having witnessed unspeakable horrors and devastation. Many had to flee with no notice, leaving behind husbands, fiancés, brothers, sons, daughters, and elderly or disabled parents. Many more have lost family members and loved ones. Few who have been granted protection in the U.S. would want to willingly return to their home country or to a third country where loved ones are sheltering, in which they have no comfort or permanent protection. It is imperative to expedite their advance parole travel authorizations in order for them to be able to make these stressful trips timely and return to the U.S. as quickly as possible.

Moreover, with the significant increase in humanitarian parolees in recent years, including those entering through the newly launched Venezuelan parole program, there will be a greater need than ever to be able to expedite processing for advance parole travel authorizations. The nature of humanitarian parole is by definition a short-term entry. Accordingly, time is truly of the essence for processing their advance parole applications.

By the same token, those who recently arrived and find themselves in need of having to leave the protection of the U.S. often have no financial means to pay the $575 application fees for each member of their family who must apply to travel. This poses an undue hardship for those who have to make a choice between paying for housing, food, and necessities, or paying application fees that may not receive a determination for months. Some of them will be forced to engage in unlawful employment or other prohibited activities just to have a chance at leaving the U.S. lawfully to see ill or dying relatives.

Legal Justification: USCIS has authority to designate certain immigration forms for online filing at its discretion. Allowing applicants to file for advance parole online would help automate the processing for humanitarian parolees. Those applicants’ biometrics are already in the DHS database, so extensive security vetting should not be necessary.

Likewise, USCIS has regulatory authority to designate any immigration forms it deems appropriate for fee waivers. Granted, such actions could be subject to rule changes, but there is little risk of outside stakeholders responding to notice and comment with adverse reactions to proposed eligibility for fee waivers for advance parole travel authorizations. On the contrary, many immigrant communities and refugee assistance groups would welcome such a change.

Precedent: There is ample precent for both expediting processing of certain forms and/or applications from certain categories of applicants. There is also ample precedent for allowing certain forms to be eligible for fee waivers.

For more information on these and other advocacy initiatives, please email [email protected].